Five Blue Marlin Stranded on WA's Southern Beaches

Redmap WA and Kieryn Graham, 10 Jul 2014.

Lat year Redmap received a series of rather peculiar reports in Western Australia. Beach goers along the south coast stumbled across not one but five enormous, yet stranded blue marlin. With winter upon us once again, should people be on the lookout for similar occurrences this year?

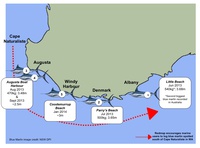

In January this year, another massive blue marlin (Makaira nigricans) washed ashore at Coodemurrup Beach, near Windy Harbour (pictured above) bringing the tally to five blue marlin strandings on Western Australia’s southern coastline in just 8 months. Could this cluster of strandings be a symptom of a changing ocean, a result of something more sinister or just a case of better reporting?

It all began in June 2013 when an Albany local stumbled upon the second largest blue marlin ever recorded in Australian waters struggling in the shallows of Little Beach at Two Peoples Bay. Understandably, this caught the attention of many people in the community including Tahryn Thompson, Marine Education Officer with the Department of Fisheries.

“It was a truly enormous specimen and the photos just don’t do it justice. We were able to determine the marlin weighed 540kg - only 17kg off the Australian record”.

“Just as the excitement wore off the first stranding we got word that another blue marlin, nearly as big as the first, washed up on Parry’s Beach in Denmark. Subsequently, two more blue marlin washed up in Augusta in August and September last year”.

Indeed, these strandings occurred at the southernmost tip of the marlin’s natural range, which is thought to extend from Albany in Western Australia’s south upwards into the tropical Indo-Pacific and on the east coast from Mallacoota in Victoria to the northern Great Barrier Reef. Blue marlin seldom frequent waters below 20°C and the range and movements are not entirely clear. Redmap encourages members of the community to log any blue marlin spotted south of Cape Naturaliste in West Australia.

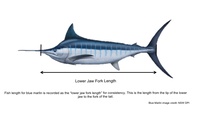

Blue marlin can reach up to 5 metres in length and the current record for the heaviest ever recorded is a gigantic 629kg fish caught in Hawaii. Interestingly, blue marlin that weigh over 180kg and thus all five fish stranded in Western Australia in the last year, are generally all female.

So many strandings within such a relatively short period of time has raised several questions. First, what change or changes within our marine environment are precipitating these strandings and second, should we be concerned?

Strandings, although unusual in the sense that they are all relatively close together, are not unprecedented. Mrs. Thompson suggests that the actual number of historical strandings of marlin might be more that has been officially reported.

“As we talked with more long-term residents on the south coast we discovered that there had been similar strandings in the past”.

“In 1987, a 3 metre long marlin was recorded at Parry’s Beach in Denmark. Later, in 2010 a blue marlin measuring over 3 metres in length was recorded at Norman’s Beach in Albany and another at Parry’s Beach in Denmark in 2012,”

“These unreported strandings illustrate what an important tool Redmap is to share local knowledge and record valuable data in the midst of ocean warming,” she says.

Queensland-based Dr. Julian Pepperell (Pepperell Research and Consulting) is an Australian marlin expert. He also believes that there is no need to worry, or at least not yet.

“Very large marlins are also known to occasionally occur at the extremes of their distribution. This is because their large body mass to surface area ratio permits them to tolerate colder waters where they are able to hunt with less competition”, he says.

It is unclear whether blue marlin strandings are on the rise as a result of ocean warming.

He said it could simply be a case of these tropical fish hitching a ride down the coast of Western Australia in the warm Leeuwin Current and then subsequently getting trapped within the colder than tolerable southern waters. According to Dr. Pepperell this is very plausible for larger pelagic fish like blue marlin.

“As warm currents travel down the coasts of both western and eastern Australia, large eddies of warm water often break away, and continue moving south, but surrounded by colder water. If tropical/temperate fish such as marlin and tuna are in those eddies, they will eventually be exposed to colder water as eddies break up”, he says.

“When this occurs it is unclear whether many of these fish simply perish or head north in an attempt to find warmer water”, he says.

Dr. Pepperell concludes that, “If these ‘boundary riders’ become isolated and find themselves in colder than tolerable water, they very likely become disoriented. This seems to be the likely cause of the Western Australian strandings, since blue marlin would normally never be found in shallow water close to the coast.”

Whether the frequency of blue marlin strandings is increasing as a result of ocean warming is yet to be demonstrated. Continuing to log reports via Redmap is vital to contribute to the understanding of how warming ocean temperatures could be impacting our marine species, including blue marlin. Continue to check the Redmap website regularly and keep in touch through Facebook to see what interesting ‘beachcombing’ reports are logged over winter.