Squid: the biology basics

The Redmap Team.

Squid belong to a group of animals called cephalopods, which includes octopus, cuttlefish, and nautilus. In Australia, we have both the smallest squid in the world, the pygmy squid at 2cm, and the largest squid – the giant squid, with squid rings as big as truck tyres!

From a biological perspective, squid are rather bizarre creatures. They have not one, but three hearts - one at the base of each of two gills to pump deoxygenated blood through the gills, and one main heart to pump oxygenated blood through the rest of the body. Squids have such high metabolic rates that they need to extract oxygen through their skin surface as well as through their gills. To provide fuel to support their fast metabolism and fast growth rates, squid must consume huge amounts of food each day. They eat pretty much anything that moves, and tear apart their prey with their parrot like beak. A beak to chop their food into tiny little pieces is essential, as their digestive tract actually goes through a narrow channel of cartilage in their brain to get through to the stomach!

Squid are very intelligent creatures with a nervous system as well developed as fish, and more advanced than that of any other invertebrate. As they have such a developed nervous system, it’s a good idea once you’ve caught a squid to try and kill them as humanely as possible - either place the squid in an ice slurry which dulls the nervous system before killing them, or remove the head straight away so that it dies very quickly. When squid themselves are ‘fishing’, they actually kill their prey very quickly as well, by biting through the back of the neck of the fish to take out the spinal cord and stop them from struggling. You couldn’t exactly call them compassionate creatures though – if they are hungry enough with no sign of dinner in sight, they will quite happily turn around and eat their closest squid neighbour.

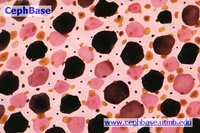

Vision is a sense especially highly developed in squid, and this is why their eyes take up such a large proportion of their head. Squid need highly developed vision as they communicate with each other through changes in body colour patterns and posture. The surface of a squid’s skin is covered with pigment filled sacs called ‘chromatophores’ and each sac has independent neural control so that the squid can expand or shrink each chromatophore (see image left). By expanding or shrinking all the chromatophores over the body surface, squids can produce many different patterns from ghostly white, to all black, blotchy dark spots, or big thick zebra stripes. Squid can change the patterns on their body in a millisecond - more rapidly than a chameleon can.

Some other squid facts:

- Squid have 8 arms and two longer tentacles. The tentacles are used to capture prey and the shorter arms are used to manipulate the food

- Each individual sucker on their arms can be independently controlled and moved

- All squid are carnivorous predators with huge appetites

- Squid move by either moving their fins, or by jet propulsion

- Squid use a smoke screen to evade danger – they squirt ink out of their ink sac

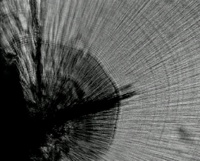

- Squid can grow really fast – southern calamari can grow from a 5mm hatchling to a 400mm adult in less than 1 year. To tell how old a squid is, or to see how fast it has grown, we look at small bony structures in their heads called statoliths (see image left) or earbones. Statoliths have tiny growth rings in them – one per day, and by counting the rings we can see how old a squid is.