Climate change on the Apple Isle’s doorstep: EAC warms Tasmanian waters

Dr Eric Oliver.

Tasmania's east coast is considered a global warming hotspot with waters warming up to four times the global average. Why are Tasmanian waters warming so fast?

The waters off the east coast of Tasmania have been warming dramatically over the last several decades. The region is one of several “hotspots” around the globe where waters are warming up to four times faster than average (Holbrook and Bindoff, 1997; Ridgway, 2007).

We know this is happening because scientists have measured the warming itself, particularly from a long-term measurement site near Maria Island, and also because of the dramatic impacts to Tasmania’s cool-water marine ecosystems. Two examples that stand out are the loss of giant kelp and an increase of warm-water intruders like the spiny sea urchin.

What makes eastern Tasmania so special? Why are the waters there warming up so fast?

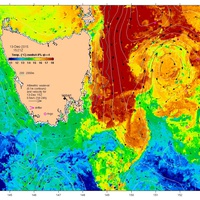

The East Australian Current, or EAC for short, is a strong seasonal ocean current that brings warm water down the east coast of Australia, as far south as Tasmania over the warmer months. It’s because of the EAC that water temperatures off the east coast tend to be warmer than the rest of the state. Some years this current is particularly strong, such as in the summer of 2015/16 when the waters off eastern Tasmania were extremely warm – so warm in fact that even the swimmers and surfers noticed it. Waters were three degrees warmer than usual, so it would be hard not to notice!

Besides these year-to-year changes in EAC strength we have also noticed that the EAC has regularly been getting stronger over the last few decades. This increase in the strength of the EAC brings more warmer water further south along the east coast. The EAC now reaches 350 km further south compared to 60 years ago (Ridgway, 2007). The extra warming from the EAC has been on top of the average warming the whole globe has experienced. The combination of background warming and a strengthening EAC makes eastern Tasmania a global warming hotspot. But why has the EAC been increasing and will the trend continue?

The long-term strengthening of the EAC is related to human-driven climate change. We tend to think of climate change as global warming only, but many other aspects of the climate have also been changing, including changes in storm events, rain, and wind. And of course, in the behaviour of ocean currents.

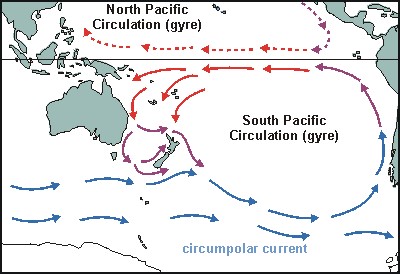

The wind over the South Pacific Ocean drives the South Pacific gyre, a huge whirlpool of water that stretches between Australia and South America, and the EAC forms the western limb of that gyre. With climate change, the winds over the gyre have been getting stronger which drive a stronger gyre, especially in the south, which in turn drives a stronger EAC down towards Tasmania (Roemmich et al., 2005).

Image above: Currents in the Pacific Ocean are influenced by winds, which are changing with a warming climate. (http://www.seafriends.org.nz/issues/res/pk/ecology.htm)

Future projections of climate change into the 21st century suggest this increase in the EAC will continue for the foreseeable future. This means we should expect more warming off the east coast of Tasmania in the future, more impacts to our cool-water ecosystems, and more intruders from warmer waters. So what sort of marine future can we expect off the east coast of Tasmania in the coming decades? This is a question that researchers are trying to tackle now.

Holbrook, N. J., & Bindoff, N. L. (1997). Interannual and decadal temperature variability in the southwest Pacific Ocean between 1955 and 1988. Journal of Climate, 10(5), 1035-1049.

Roemmich, D., Gilson, J., Davis, R., Sutton, P., Wijffels, S., & Riser, S. (2007). Decadal spinup of the South Pacific subtropical gyre. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 37(2), 162-173.

Ridgway, K. R. (2007). Long-term trend and decadal variability of the southward penetration of the East Australian Current. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(13).

Dr Eric Oliver is a Research Fellow in Physical Oceanography at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science (ARCCSS) and the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania. He researchers ocean and climate variations and their predictability. Check out his IMAS profile here: http://www.utas.edu.au/profiles/staff/imas/eric-oliver