A fish by any other name

Redmap Team.

A fish by any other name…would just confuse everyone…but given people refer to a single 'snapper' species as bream, cockney, cockney bream, cockney snapper, golden snapper, old man snapper, pink snapper, porgy, red bream, red pargo, sea bream, squire, or squirefish....we thought we'd visit what goes into naming a species.

In light of a recent species name change, we thought we’d visit species naming: – what goes into it, who does it, and why it’s so important.

Snapper, pinkie, red bream, squire, old man red snapper…. The list goes on for the different ‘common names’ that people use to refer to a single species (thumbnail image left; snapper, Chrysophrys auratus). Scientists have only ONE scientific (Latin) name for each species – which means that scientists around the world all use the same name. So this allows scientists across the globe to be able to talk about a particular species (despite language barriers and different common names) – and each know exactly what they’re talking about!

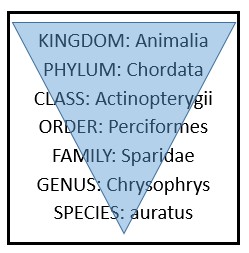

“Binomial nomenclature” as it’s called, is the formal system of naming a species. A species name actually comprises two parts: Genus and species. So for example, the scientific name for snapper, pinkie, red bream, squire, old man red snapper is actually Chrysophrys auratus (Chrysophrys is the genus, and auratus is the species, thumbnail image).

Well, technically scientists use one at any given time…but it may change. For the last few years, Redmap (and scientists around the globe) has listed “snapper” as Pagrus auratus. Recently this name changed and is now Chrysophrys auratus. Indeed, it has actually reverted back to a previous name – but that’s not the point. The interesting part is how species get their name in the first place, what causes these to change (and change back!), and what on earth do we do if we find a species that’s never been properly defined (which happens more than you think….).

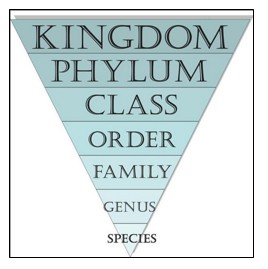

In biology, species are grouped by relatedness. Species within a given genus are more closely related to each other than they are to species in a different genus .. see Figure 2 – where animals (and plants) are classified in a hierarchical system in groups of shared characteristics.

So how exactly is it done? The International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature oversees the process worldwide. It ensures that every species has a unique scientific name (that is accepted globally – so even if two countries have the same species, they are always the same name). This process is called taxonomy – and itself is a constantly changing field (as we learn more and develop new ways for looking at genetic diversity). Each species is based on a “type specimen” – one particular specimen that is used for genetic analysis and usually kept in a museum (sometimes an image is used as the type).

Figure 2 (right) shows the classification of animals. Kingdom is the broadest category (e.g. plants and animals are separate kingdoms). This means that every species has a classification for each level of the pyramid….and the more levels that are the same, the closer they are related. For the snapper example, the classification is below.

Cataloging species correctly, and in terms of Redmap – making sure we use the correct Latin name - is crucial. People often use different common names for the same species – so without a standardised way of naming, species identification would be confusing and unreliable. For example, what someone calls a pinkie in Tasmanian might be different to what someone calls a pinkie in Victoria…

This may have you now wondering how we choose the common names we decide to use on our website (snapper, pinkie, red bream, squire, or old man red snapper?). Redmap, like many other science programs, uses a consistent standard. For this we use Codes for Australian Aquatic Biota (CAAB; http://www.marine.csiro.au/caab/). This is a coding system developed by the CSIRO Division of Marine and Atmospheric Research, Australia (CMAR) for Australian aquatic animals, and is a consistent way for defining a common name.

References and further reading:

http://museumvictoria.com.au/about/mv-blog/apr-2012/so-many-specimens/

http://australianmuseum.net.au/snapper-pagrus-auratus-bloch-schneider-1801

http://www.fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/678

http://animaldiversity.org/animal_names/scientific_name/

http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=367239

http://reeflifesurvey.com/species/1713/